What Feeds Creativity (and what kills it)

Notes on cultivating curiosity, accepting fear, and protecting your creative energy.

To say that the post-holiday sedentary slumber reversed itself quickly over the past week would be an understatement. After returning from the Berkshires for work on Tuesday, I dove directly back into one of our busiest weeks of the year at the office, bookended by workouts every morning and plans every evening—long overdue catchups, a book event for Laura Dave’s latest at The Strand, and a gorgeous dinner with West Village Book Club. Basically, we’re back to our regularly scheduled programming. That is, chaos!!!! Just the way I like it.

Last Sunday’s letter, The 26 small upgrades that make my everyday life a whole lot better also took on a life of its own this week, now having reached 12k+ readers and counting. Y’all reallyyyyy seemed to especially enjoy my section on wearing actual pants to the airport (!!), with dozens joining me as proud members of the sweatpant jeans club. I’ll be sporting mine on my flight to LAX next Sunday, so it seems fitting!

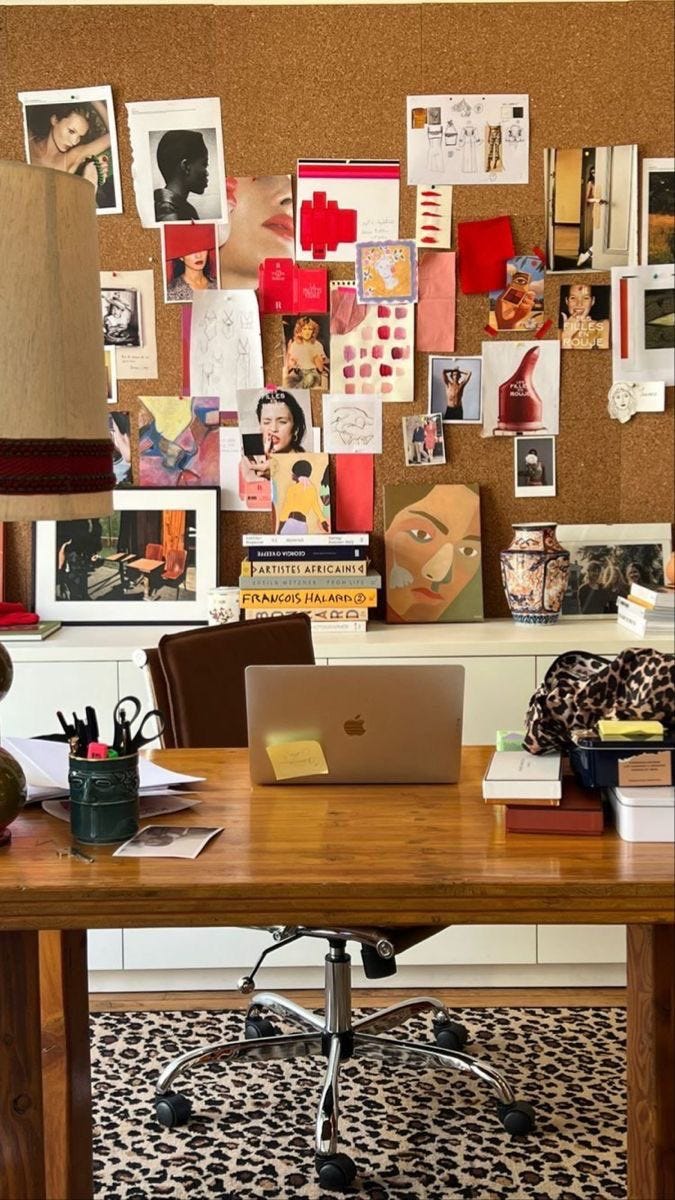

What feeds creativity

What kills creativity

The Vault (Paid Subscriber Exclusive): What creativity looks like in this season of my life

Today’s letter focuses on a topic I ruminate on often: what feeds creativity, and, conversely, what kills it. Each January 1st, I queue up my audiobook of Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear by Elizabeth Gilbert. It’s a quick listen—just about 3.5 hours—and despite this being my fourth time revisiting it, I continue to take away new tidbits.

Gilbert (yes, the Eat Pray Love one, but also, so much more!) approaches creativity less as something you summon and more as something you host. A presence that shows up when it feels welcome—and quietly disappears when it doesn’t. She treats ideas as living autonomous entities, and the incredible story she shares about an idea that came knocking at both her and Ann Patchett’s door is reason enough to read the book.

Her approach poetically reframes creativity not as something that requires suffering or genius, but as a force that welcomes curiosity and play. Her central idea that fear is allowed to come along for the ride, but not be in the driver’s seat, has a way of sticking with you. Coming off this latest re-read, I felt compelled to summarize what tends to feed my creativity in general and what reliably shuts it down. Consider this less advice, more an inventory—ingredients to check your creative pantry for in 2026.

But first, a broadening of your definition of “artist.”

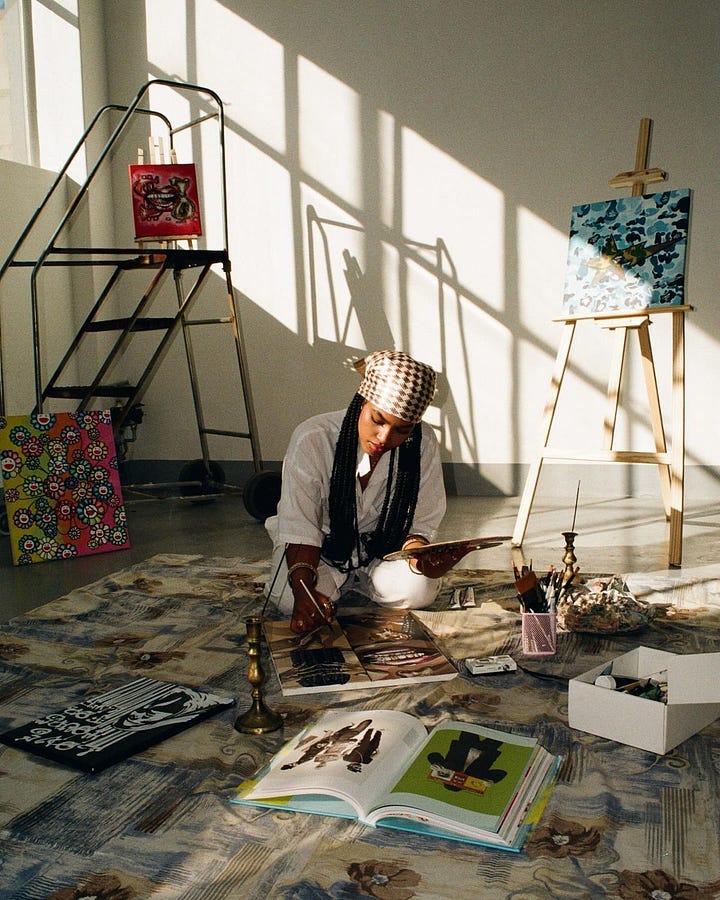

In Big Magic, Elizabeth Gilbert is careful to define creativity broadly. “Art” isn’t limited to writing books or making art in the traditional sense; it’s any act driven by curiosity rather than obligation. Creativity shows up in how you solve problems, how you host a dinner, how you build a business, and ultimately, how you make meaning out of everyday life. Basically, whether or not you know it, you are an artist.

Seen this way, creativity isn’t reserved for artists in the traditional painter, sculptor, writer sense—it’s available to anyone willing to pay attention. Creativity lives in choices, conversations, and experiments just as much as it does in finished work. Framing creativity this way removes the pressure to “produce” something impressive and instead invites participation, however small or personal that may be.

Curiosity over outcome.

Creativity thrives when the question is “What am I interested in?” rather than “How will this be received?” Outcome-driven thinking tends to constrict and manipulate things before they’ve had a chance to unfold. Curiosity, on the other hand, creates room for exploration without expectation.

Low-stakes creation.

The kind of making that isn’t trying to become anything is often where the most meaningful projects begin: an idea jotted down on the back of a napkin, knitting a garment knowing it’s not going to be perfect, a watercolor that quite literally goes outside the lines. Gilbert reminds us that creativity doesn’t need pressure to survive—it needs the opposite. Lower the stakes, and the work begins to breathe.

Creating before consuming.

Creativity often needs a moment of quiet before it can make itself known. Beginning the day without taking in other people’s ideas is the surest way to actually give your own a chance to surface. When the metaphorical room is already full, it’s hard to hear what an idea is trying to tell you. Not to mention, the sheer hours we spend (waste?) on scrolling and consuming take away from the practical possibility of carving out time for art. Personally, this category presents my largest area of opportunity to shift how I’m operating.

Don’t expect your art to pay your rent.

In Big Magic, readers are reminded that creativity struggles when it’s asked to be everything at once—meaningful, profitable, and identity-defining. There’s a difference between making money from creative work and asking that work to sustain you, financially or emotionally. When art is relieved of that burden, it stops negotiating and starts offering. Ideas tend to arrive more freely when they’re invited, not depended on.

Pursue creative cross-pollination.

Creativity expands when it’s allowed to borrow language from elsewhere: reading outside your usual genre, visiting museums unrelated to your medium, talking to people who don’t do what you do. These moments of newness spark inspiration and introduce new textures without demanding output.

Give yourself permission.

The radical idea that you’re allowed to make things simply because you want to is a huge step in embracing your creativity. Not because you’re an expert. Not because you’re ready (what does that even mean, after all?). Just because you’re curious.

Waiting for the confidence.

Confidence is not the prerequisite; it’s the byproduct of actually doing the thing. In Big Magic, Gilbert is clear that creativity doesn’t wait for certainty before showing up. Waiting to feel ready often means waiting indefinitely. Remember, “ready” isn’t a feeling—it’s a decision.

Over-identifying with the work.

When output becomes a proxy for your worth, creativity gets stage fright. Suddenly, every idea feels like a referendum rather than an experiment. The work tightens under the pressure of having to represent who we are as people. There’s something quietly romantic about having a private creative outlet—one that exists without witnesses, fueled in the margins of your day, owing nothing to anyone else.

Turning creativity into a performance review.

Metrics, optimization, comparison—all useful tools, but terrible muses. When the work is constantly assessed for effectiveness or reach, experimentation narrows. Creativity struggles when it’s treated like a quarterly report. It’s difficult if your outlet involves any level of external readership or viewers in order for it to exist in the world to step away from the analytics; in my case, for instance, with TSS, I want people to read and interact with it! But just because a post doesn’t get “engagement” actually doesn’t mean the writing was any less valuable to me as the creator.

Perfectionism dressed up as “high standards.”

The one that masks as responsible, even virtuous, but is often just fear with better branding. As a lifelong ‘perfectionist,’ I’m making an active choice to be rooted in “done is better than perfect” with all I create. Ideas rarely survive long enough to become themselves in environments where we are hypercritical, so sometimes, the freedom that comes from simply finishing something (even when you know it could be better) is the ultimate embodiment of creativity.

In this season of life, my creative well feels closely tied to the tension I’ve learned to sit with between expansion of self and protection of self. On one hand, I feel a genuine pull to create more—to experiment with new formats, to make silly TikToks, to show up more visibly and honestly. On the other hand, I’m deeply aware of the stability my full-time job provides, and how much peace and, in turn, steadiness it affords me. I’m not willing to post or share anything that would threaten that.

The desire to build creatively alongside the fear of threatening something so stabilizing can feel like I’m constantly pulled between two opposing forces.

For a long time, I thought this meant I had to choose—either protect the structure I’ve built at all costs, or risk it in service of creative expansion on my personal projects. These days, I’m clearer than ever about the possibility that sits in the middle, having finally found the boundary between the two. I know how to pour my creative energy into both the job that allows me to move through the world the way I do and the content I create, separate from that.